LONDON – Almost all political movements soften their influence over time. As the mainstream changes, the razor’s edge of contemporary debate becomes part of a longer timeline. By the time artistic production becomes a museum, it is over, firmly locked in the past. Women in rebellion! Art and Activism in the United Kingdom 1970–1990 is a classic example of this: a massive spectacle covering British feminism from the 1970s to the 90s, pressing different groups and causes into a neat timeline.

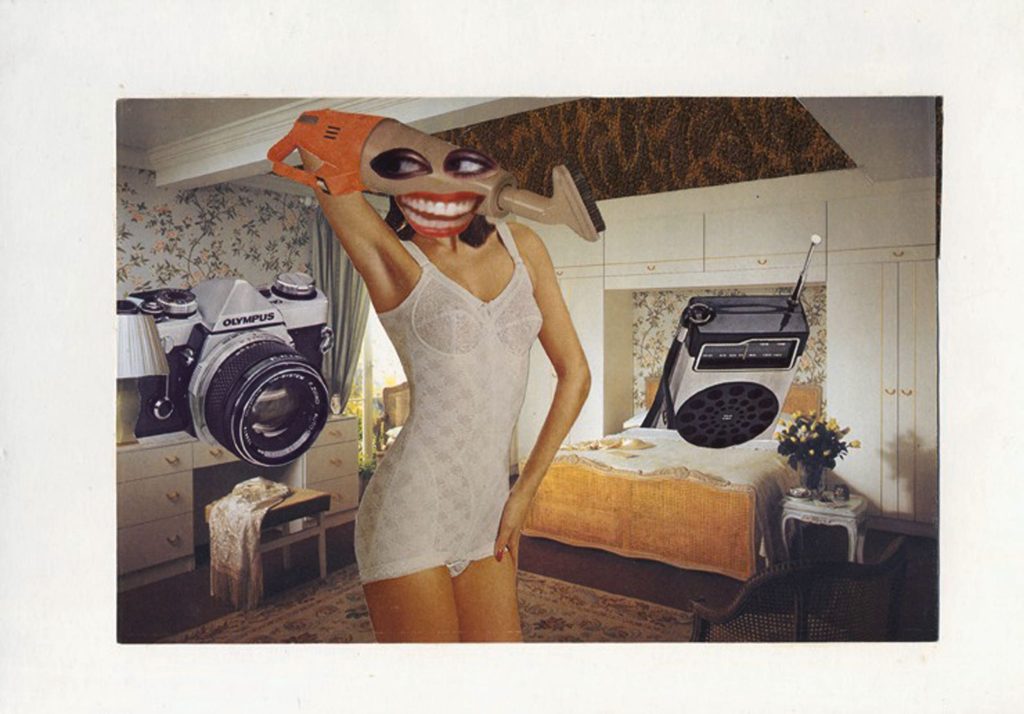

This exhibition occupies the large galleries on the ground floor of Tate Britain and is overflowing with material, much of it borrowed, for whatever reason Tate has not seen fit to welcome these artists. It is unusual in that it relies on documentary photographs and archival materials, including films and ephemera. Susan Hiller, Lubaina Himid, Claudette Johnson and Sutapa Biswas produced a number of works for art spaces in the exhibition, but they are shown alongside more photojournalistic works, as with the series. Who is holding the baby? (1975), a study of the lack of childcare in East London by the women’s collective Hackney Flashers.

Such a dense exhibition of archival material Women in Rebellion it does two things. First, it emphasizes the role of creative production in political movements: banners, flyers and performances are rightly considered artistic works in the service of radical change. Second, and more insidiously, it risks reducing these movements to being visible and archiveable, and turning them into an aesthetic experience. The exhibition opens with photographs from the first Women’s Liberation conference, alongside photographs of Anne Bean’s “Heat” (1974–77) and “Shouting ‘Mortality’ as I Drown” (1977). Looking at these sets of images requires a similar imaginative process, remembering that they are a reflection of an event and not a reflection of the whole.

A later episode, titled “Greenham Women Are Everywhere,” documents the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. From 1981 to 2000, the group blockaded Greenham Common Royal Air Force base to protest against the nuclear missiles stored there. The Peace Camp is represented Women in Rebellion through black and white photographs of anti-base actions and daily activities of demonstrators, as well as banners and performance tools. There is also Margaret Harrison’s “Common Reflections” (2013), a recreation of a section of the fence surrounding the site, which protesters hung with treasures and everyday objects. This work is direct memory, recreating Greenham’s appearance without its social context. In the gallery, the spoons, photos and clothes hanging from the chain link fence are really things to look at, a reflection.

Tate Britain is an art museum, so that’s only natural Women in Rebellion it would focus on artists’ responses to political events. The national exhibition is also narrow: the remit of the exhibition is centered on Great Britain, creating an artificially insular narrative given the internationalism of many of the featured artists. An exhibition cannot be expected to tell a global story, but the Tate emphasizes that “the women of Greenham saw their anti-nuclear position as feminist” and devotes two rooms to the British Black Arts Movement, without giving space to its contexts and international networks. these artists were part of it.

Something strange happens when activism enters the exhibition space. The institutionalization of radical history inevitably blurs the message, and simplifies the complex whole into a specific lineage. There is no easy way to represent the breadth and significance of a political movement in an art exhibition, nor should there be. However, the way the archival material is presented Women in RebellionThrough documentary photography and transitory displays shown alongside more conventional artistic responses, creative production appears to be the same as direct action. This is unfair to artists who keep political engagement out of their art, and it aestheticizes protest participants like Greenham, turning their actions into performance.

An occupation of Greenham’s scale and duration is almost unthinkable now, at a time when the British government considers even the most peaceful protests a threat to national security. Women in Rebellion he makes oblique allusions to the violence these artists endured—gendered, racialized, homophobic—and alludes to the Greenham arrests and anti-racist uprisings throughout the period. It is up to us as visitors to see how the violence underlies everything in this show, to know how the present flows, to learn from events like Greenham’s as a performance as well as to experience them. against the war

Women in rebellion! Art and Activism in the United Kingdom 1970–1990 It continues at Tate Britain (Millbank, London, England) until April 7. The exhibition was curated by Linsey Young, Zuzana Flaskova, Hannah Marsh and Inga Fraser.