Artist Richard Serra, whose monumental sculptures distort the sense of space and time, died at his home on Long Island, New York on Tuesday, March 26. He was 85 and the cause was pneumonia, his lawyer John Silberman said. New York Times.

Serra was born in San Francisco in 1938 and graduated in English from the University of California, Santa Barbara, before studying painting at the Yale School of Art and Architecture, primarily under the tutelage of Bauhaus alumnus Josef Albers. Despite his basic training in two dimensions, Serra became famous for his sculptural works, particularly massive installations made of cold-rolled industrial steel, gently bent or elegantly coiled into spirals. Large and imposing, at the same time aloof and attractive, they remind us of sublime universes waiting to be discovered, rather than works to be seen from afar.

The artist made his home in New York City in the mid-1960s, when Minimalism was being embraced as a fresh alternative to passionate abstract expressionism. Unlike his contemporaries, however, Serra opted for the rigorous and process-based over the smooth and precise. It was during this time that he created his so-called “Verb List”, writing down 54 actions such as “twist”, “mumble”, “rotate” and “stretch” and instructing his art materials to obey each one. .

Today, a social media search for “Richard Serra” turns up a steady stream of reverential, slow-motion selfies and videos, many of them filmed at Dia Beacon, where the artist Torqued Ellipses (1996–2000) and other works look at the long term. But these pieces were not always so well received. The 12-foot-tall, 120-foot-long, rusted plate of weathering steel called the “Tilted Arc” was met with reactions ranging from dismay to anger when it was unveiled in Manhattan’s Foley Federal Plaza in 1981. Nine years and a contentious lawsuit later, the artworks were removed from hundreds of government employees who petitioned for their withdrawal, stored away and never publicly displayed again.

Criticism has made much of the relationship between Serra’s use of scale and the vision of his work. Hyperallergic Contributor David Carrier characterized Serra’s 50-ton Forged Rounds (2019) as “the ultimate billionaire’s art”, they are “luxurious for their heavy weight”. In one case, the sheer mass of one of these monstrous pieces — arguably the basis of their appeal — killed an employee of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1971. (The developer, not the artist, was ultimately held responsible.)

Serra’s works on paper throughout his practice, mostly using black oil sticks and crayons to engage in furious monochromatic marks, left some of us fans of his sculptures feeling disillusioned and confused. However, the artist supported these gestures, and the rich material works bear witness to the artist’s rebellious spirit.

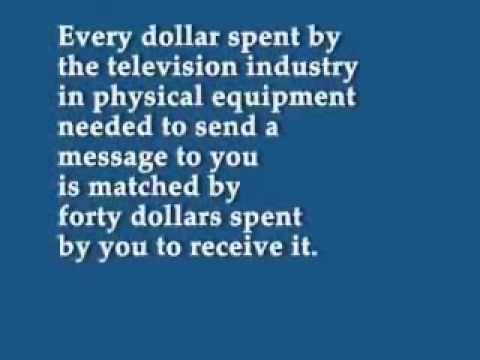

Perhaps Serra’s most underrated work is his short video Television provides people (1973), produced in collaboration with Carlota Fay Schoolman. The seven-minute piece, a critique of the mass media in the style of a public service announcement, set to a strange soundtrack of elevator music, was broadcast to the public – a successful case of inserting itself into mainstream channels to subvert and disrupt them.

“His work is literally involved in the world,” said Hal Foster in an interview Hyperallergic Editor-in-Chief Hrag Vartanian in 2019. “The key moment is when he goes out into space, first in the gallery and then in the city and then in the landscape, and when he inserts his works.”

“That’s where I think it comes to square the circle, the old opposition of autonomy and commitment,” Foster continued. “In a way, it plunges the abstraction back into the world, and thus complicates it.”