New digital art experiences, such as London’s Outernet, have been in the headlines recently with high numbers of attendees compared to more traditional museums; last year, for example, Outernet reported almost 6.3 million visitors compared to 5.8 million for the British Museum.

But how does Outernet account for visitors entering its open-sided building at a busy intersection in central London? It uses video surveillance. Or, more specifically, it uses video analytics provider BriefCam to track visitors using deep learning, an artificial intelligence (AI) method that teaches computers to process data like the human brain.

We are able to track gender and are exploring sophisticated methodologies around dwell time

Outernet representative

A clip on the company’s website asks, “What if you could drive the exponential value of your video content by making it searchable, actionable and quantifiable?” as a man behind a computer zooms in on freeze frames of faces and car license plates. Forensic investigations, vehicle make and model recognition and facial recognition are among the services offered by BriefCam, along with crowd management and “guest engagement”.

“We’re able to track gender and we’re looking at even more sophisticated methodologies around dwell time and how audiences are influenced by what they come to see, time of day, weather and moments in the cultural calendar,” says an Outernet representative. “We are proud to be working to provide some of the most advanced campaign reporting in the world. This, in addition to neuroscience research launched last year, as well as our traditional research methodologies, including qualitative and quantitative local audience measurement, gives us strong insights into visitors and their experiences.” They added that all data recorded by Outernet is “anonymized and of course protected”. .

BriefCam said Art Newspaper that it draws the line on race tracking, which is consistent with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ban on “processing personal data that reveals racial or ethnic origin”. The company added, “BriefCam’s hope is that users apply technology in accordance with applicable laws and while protecting civil rights. We are committed to protecting privacy, preventing abuse, and the ethical and responsible use of surveillance technologies.”

The private Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland, uses BriefCam to increase security, implement “intelligent workflows for better visitor experiences,” BriefCam explains on its website, and track real-time occupancy in its galleries and spaces. If someone gets too close to a piece of art or strays from the outdoor walkways, the system will send an automatic alert so Glenstone can “respond to the behavior to preserve property, safety and ambiance.”

V-Count’s Nano people counting sensors enable GDPR compliant image processing Photo: © V-Count

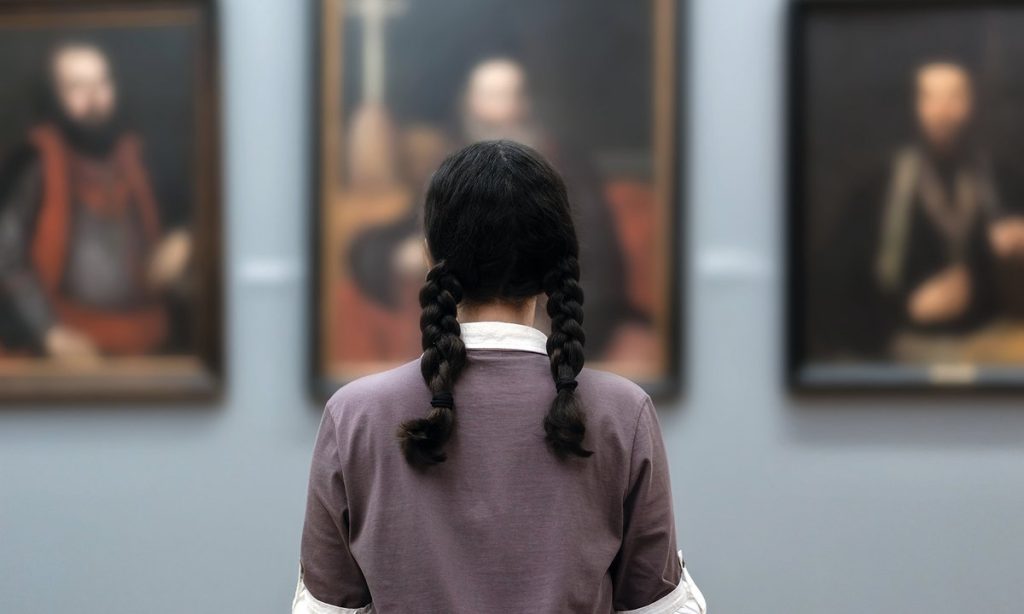

Some museums, however, are only concerned with using technology to accurately count visitors. back in 2018, Art Newspaper has revealed that faulty equipment provided by an outside company to London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG) failed to register more than 600,000 visitors in 12 months. The museum’s current crowd counter, FootfallCam, is apparently working. An NPG spokesperson says it is “based on a well-established visitor research program that provides insight into the visitor experience,” and has no plans to implement other data analytics services on FootfallCam, such as facial recognition sensors that detect “sentiment”: in other words, cameras that detect the emotion recorded on someone’s face when leaving an exhibition area to measure visitor satisfaction.

A Tate spokesman says the institution only uses cameras to count visitors and collects “more detailed information and demographic information through visitor research and surveys”. The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London uses another person-tracker called V-Count to capture footfall data in the museum’s entry-free spaces and tell it “the proportion of site visitors who do not buy a ticket”. for an exhibition,” according to an interview on V-Count’s website with Carlo Palazzi, RA’s former head of insights and analytics. The global exhibition brand V-Count is also used by art museums in the US, Asia and the Middle East, as well as the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia and the Munch Museum in Norway.

“Our innovative AI-based technology does not track or tag individuals in any way, shape, or form,” says a V-Count spokesperson when asked how it protects recorded information from potential misuse. “Then or every day he gives the main statistical data. It is important to note that these data are completely anonymized and are therefore not linked to any specific person. This ensures that our technology cannot be used for discriminatory or harmful purposes.’

The company does not disclose the locations of its servers, but emphasizes adherence to GDPR standards to ensure a high level of user data protection. “Our advanced sensors have been developed to determine gender and age without the need to capture, record, store or transfer any video or image data, so no personal data is ever captured or compromised,” added the V-Count spokesperson.