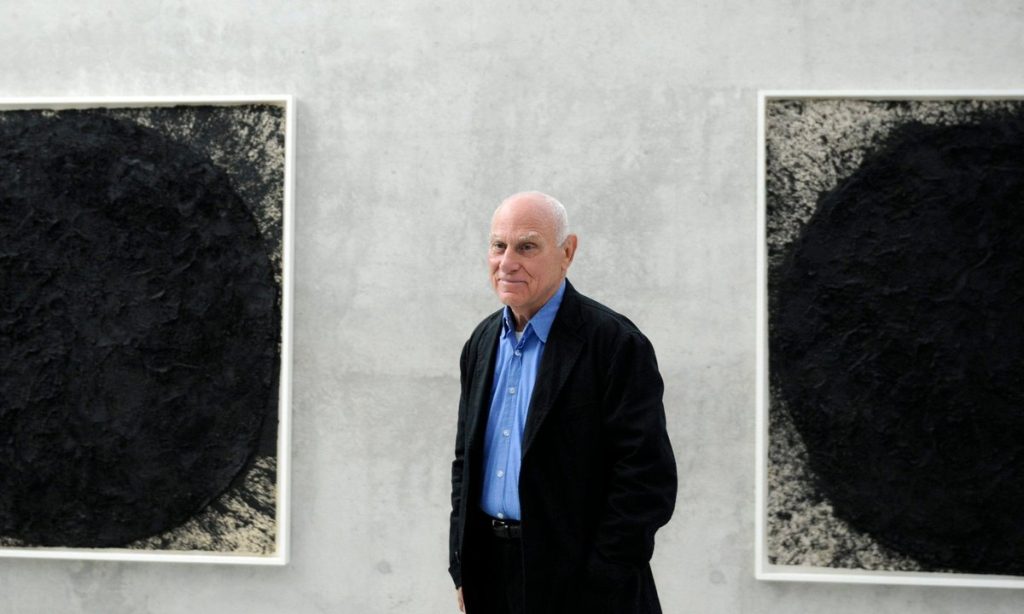

Richard Serra, an American artist who liked to “work on the edge of what was possible”, creating giant steel works on the scale of ancient monuments such as Stonehenge or Egyptian tombs, has reportedly died at his home in New York. He was 85 years old.

Serra’s oxidized steel works, which earned him the citation of being “the greatest living sculptor,” are in major collections around the world, including the Guggenheim Bilbao, where the 1,034-ton work circuit. The matter of time (2005) fills the main hall. Other pieces have been commissioned and created for outdoor spaces: the Dukhan Desert in Qatar, squares in London and New York, and atop man-made mining waste in Essen in central Germany, among many other locations.

Born in San Francisco in 1938, Serra was exposed to materials such as cold-rolled industrial steel as a child. Serra’s father, who emigrated from Spain, worked as a pipe fitter in a shipyard; his mother was the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Odessa. In a 2001 interview with former journalist and talk show host Charlie Rose, Serra recounted how his father took him to the shipyard for his fourth birthday to watch a ship launch. At that tender age, Serra realized that “an object as heavy as this could become light, that amount of tons could become lyrical”.

A sculptor, Serra initially studied English literature at UC Santa Barbara, working in steel mills to finance his studies. It was one of his literature teachers who suggested that Serra study fine arts after seeing his drawings. With that, Serra won a scholarship to study at Yale University, where he met painters including Brice Marden, Chuck Close, Robert Mangold, and Nancy Graves, whom Serra married for a short time.

After a stay in Paris, where he made almost daily visits to Constantin Brancusi’s rebuilt studio, Serra settled in New York. There, he began experimenting with other materials, making sculptures out of rubber and molten lead. He was taken over by the famous dealer Leo Castelli in 1966, although Serra refused to make easily salable works, instead pushing for increasingly larger pieces. The artist also refused to affiliate himself with a certain movement, as it arose in the wake of Minimalism.

Despite his stature and success, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2001, Serra’s public auction market has not reached such a stratospheric level, fetching $4.3 million, not surprising given the challenging nature of his practice.

His career was not without controversy either. In 1975, a rigger died when a piece of one of his works that was being installed at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis accidentally dislodged. An investigation found that the crane operator had not followed instructions properly, ending calls from art world figures that Serra should stop sculpting. He was less successful in 1985, when he made a public petition to have it removed Bent bow (1981) brought a hearing from a New York City square after people complained that it was an eyesore and a hazard. Serra sued the US government but lost and was fired in 1989.

However, opinions were in the minority, and Serra’s popularity continued to grow. In addition to winning the Golden Lion, during his lifetime Serra was recognized for his contribution to the arts with major awards from the governments of Japan, France, Germany and the United States. And the sheer audacity and monumentality of his work means he is unlikely to be forgotten. As the artist himself said: “If you make a contribution, it is very, very difficult to predict, in terms of eternity, what will last and what will not. Let’s say that this type of work means there is an opportunity.’