Famous children’s author and illustrator Beatrix Potter lived as well as one might expect. He reached an international audience from his home in the fairytale landscape of England’s Lake District, where he wandered his sheep farm, wrote letters to children and investigated the miniature worlds beneath his feet through a magnifying glass attached to a wooden walk. stick But his work is not limited to books The story of Peter Rabbit (1901) or Benjamin Bunny (1903), as of the Morgan Library Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature the exhibition makes abundantly clear, inviting visitors to gain a new appreciation for his enduring stories, steadfast dedication and endless curiosity.

Beatrix Potter was born in 1866 into a wealthy family in London, where the author lived most of her young life. He had few friends as he navigated the stifling social confines of upper-class British life and instead found solace in the natural world. Potter had at least 92 pets during his lifetime, including a pair of salamanders (Sally and Mander), a bat, a frog, at least three lizards, a snake, a duck, mice, a family of snails, and more. of course, rabbits (Benjamin and Peter were real rabbits). He carefully studied their behavior and sketched them.

Without the pressure to earn a living or marry into wealth, Potter was free to devote himself fully to his passions. As a child and teenager he drew relentlessly. In his 20s and 30s, Potter emerged as a mycologist and naturalist. “Detailed depictions of fungi such as Anainta crocea, ‘Organe Grisette’ and Amanita muscaria. ‘Fly Agaric'” (1897) is an example of his scientific skill.

Morgan Library curator Philip Palmer was unaware of Potter’s expertise in mushrooms when he began working on the show, which traveled from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London to the Frisk Museum in Nashville and the High Museum in Atlanta before arriving in NYC. But he said it was always his favorite book Story by Mr. Jeremy Fisher (1906), embark on a journey to prepare a gourmet dinner for his friends, the story of an elegant frog who loses his clothes and escapes from the mouth of a large trout.

“I asked him to read it over and over since I was a kid,” Palmer said Hyperallergic. “It was so funny to me that Jeremy Fisher wears these nice clothes – his vest – but his house is full of mud and water and at the end when he’s serving roasted grasshoppers to his friends, they get a little turned off by the food. I love the real animal instincts and the humanity. that combination of polite society.’

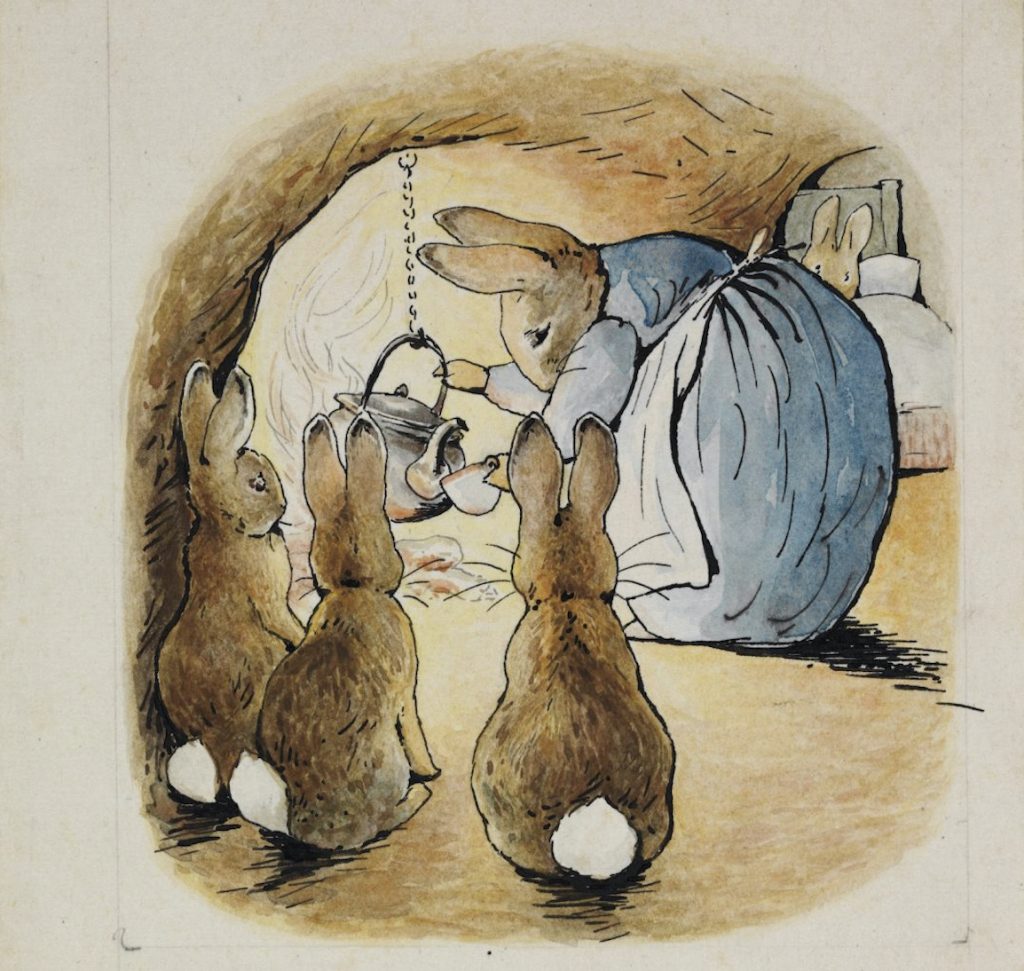

The second part of the exhibition is dedicated to Potter’s 28 children’s books, most of which were published between 1902 and 1913. Many are based on correspondence with children, and are displayed alongside recent illustrations. The show features an eight-page letter to Noel Moore, the son of Potter’s former governess. The story of Peter Rabbit (1901). Others include a series of miniature notes written in the voices of Potter characters, such as the mischievous Nutcracker.

“He wanted to enjoy the kids,” Palmer said.

In 1905, Potter bought Hilltop Farm in the Lake District, where he had been holidaying since he was 16. The animals he encountered in his new home – while dealing with a major rat problem – inspired new stories, among others. The Tale of Samuel Whiskers (1908), The story of Tom Kitten (1907), and The story of Jemima Puddle-Duck (1908). Morgan rebuilt a room from her home in the center of the gallery where children can read Hilltop Tales in a comfortable seat, next to a temporary window. Potter insisted that her books remain affordable and small enough to fit into children’s hands.

A notable illustration is a small cartoon of Little Pig Robinson, who is tricked into boarding a boat where they are to be served for dinner. He looks eagerly at the open sea. Palmer stated that his fascination with Mr. Jeremy Fisher arose from the thrill of the frog’s misadventure with death, the same kind of thrill that drives stories, for example. The story of Pig Robinson (1930) and The story of Peter RabbitPlaying chicken with the awesome Mr. McGregor.

“It’s possible to connect with another one [artists whose] it is seen that the works have cute animal characters. But I think that sells his work very short,” Palmer said, noting that Potter’s characters are not only anatomically accurate, but also follow their “true biological instincts” toward crime, often with near-destructive consequences. Nutkin the Squirrel, for example, loses half his tail and Tom Kitten is practically baked into a pastry. Palmer believes that the rebelliousness of these protagonists—a feature echoed in myths across centuries and cultures—is what makes their stories so appealing, even to children a hundred years later.

The last part Drawn to nature It delves into Potter’s final chapter. In 1913, she married local lawyer William Heelis and devoted the rest of her life to raising Herdwick sheep, a thousand-year-old breed on the verge of extinction. Potter became an active member of the community and bequeathed his land to the National Trust with the mandate that the herds be maintained in an effort to keep human farming traditions and the natural world alive. He published only a few books, but continued to tell stories to children through letters until his death in 1943.

In listing his favorite works, Palmer drew attention to the expertly crafted watercolor of a mushroom, which Potter had painted before writing the story of Peter Rabbit in his letter to Noel Moore.

“Within two days, he painted this rare mushroom in Scotland that his naturalist friend had never seen before,” Palmer said. “And the next day he writes one of the most famous stories ever written for children. What a terrible two days, right?”.