Van Gogh’s self-portrait is the perfect cover for many books about the painter. It illustrates not only the art, but also the artist. But, unfortunately, even major publishers and their famous expert writers have occasionally been tricked into choosing a misleading image: at least four fake self-portraits have been included on book covers.

The will to live

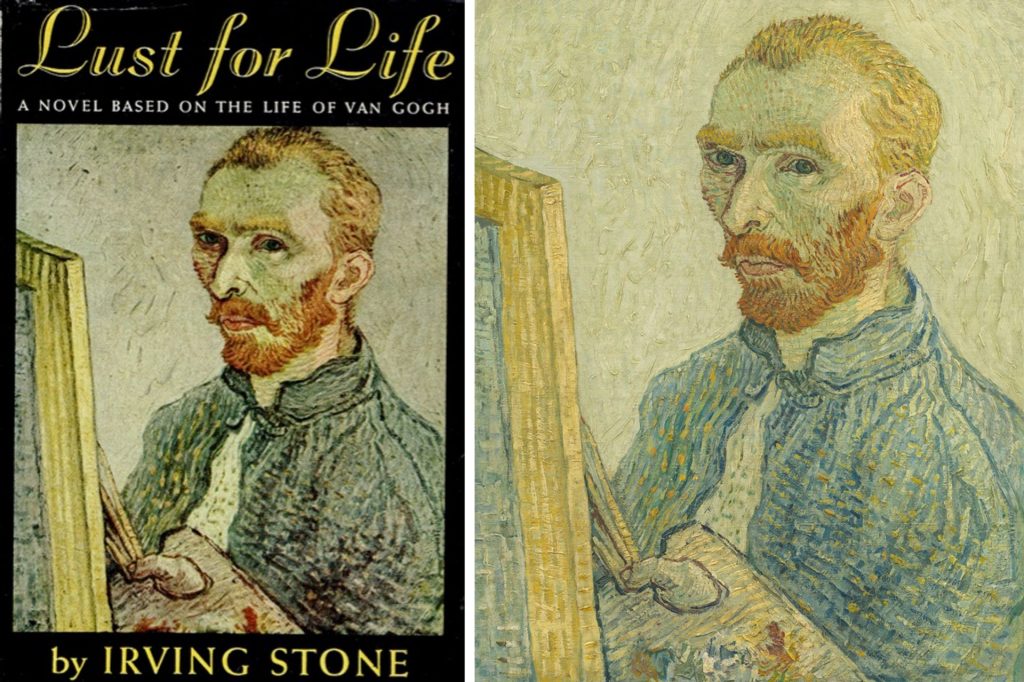

Cover of Irving’s Stone’s The will to live (1934) and the false “self-portrait” (1920s) Grosset & Dunlap, New York and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The will to live, Irving Stone’s best-selling novel, has shaped the way we perceive Van Gogh since its publication in 1934. It has been reprinted hundreds of times and extensively translated into dozens of languages. Ninety years later, it’s still in print all over the world.

One of the first editions published in New York in 1934 reproduced a “self-portrait” depicting the artist on his horse. This painting first appeared in 1928 at the Wacker Gallery in Berlin (which was later exposed for handling numerous other Van Gogh forgeries) and was quickly sold for $31,500 to American banker Chester Dale, who bequeathed it to the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1963. , DC.

Dale’s self-portrait was dismissed by most specialists in the 1950s and was left out of the work in Jacob-Baart de la Faille’s 1970 van Gogh catalog. However, the National Gallery of Art continued to claim it was genuine, presumably not wanting to offend the donor’s family.

In 1984, the gallery finally relegated the self-portrait to the status of an “imitator”.. It has since been banished to the vaults. Hopefully his appearance on the cover The will to live it was short-lived and copies of the book showing the forgeries are scarce today.

The Tragic Life

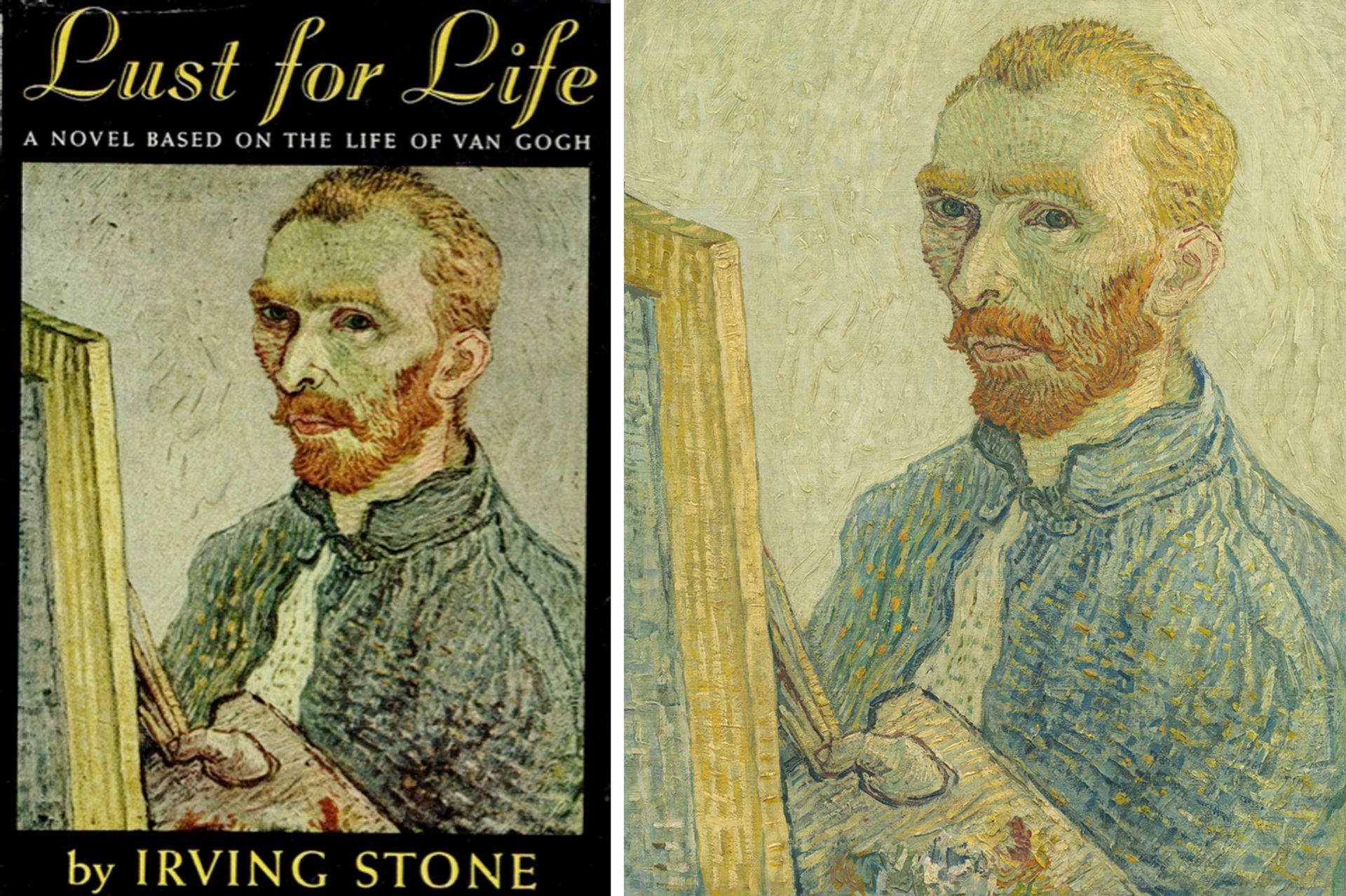

Cover by Louis Pierard The tragic life of Vincent van Gogh (1946) and a revised copy by Judith Gérard (1897 and later) after Van Gogh Self-portrait dedicated to Paul Gauguin

Editions Correa, Paris and Foundation EG Bührle Collection, Kunsthaus Zurich

A respected biography of Van Gogh by the Belgian writer Louis Piérard was first published in 1924. When it was reissued in 1946, a fake self-portrait was used on the cover. This painting has had an unusual story.

In 1898 an early admirer of Van Gogh’s work, the artist Judith Gérard, painted a copy of the original. Self-portrait dedicated to Paul Gauguin (September 1888), the original of which is now in the Fogg Museum, part of the Harvard Art Museums. Gérard created his version out of admiration, no intention to deceive.

In 1902 the painting was altered by hand and then altered by someone else, probably the French artist Emile Schuffenecker, who overpainted his signature and added a floral background. It was later fraudulently marketed as Van Gogh.

In 1911 the painting was bought by a famous Berlin collector Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, and many years later it was acquired by the Swiss arms manufacturer Emil Bührle. It is now part of his foundation’s collection and is on long-term loan to the Kunsthaus Zurich.

Although Gérard published his story about the hoax in 1931, it attracted little attention and the painting was believed to be genuine. It was tentatively accepted in the 1939 edition of the authoritative De la Faille catalog raisonné. However, by the 1950s it was increasingly rejected by specialists and was omitted from the 1970 catalog edition.

Unusually for a fake, the restored Gérard painting is on display in a museum, the Kunsthaus Zurich, but clearly labeled as a “copy after Van Gogh”. which was “reconsidered with intent to defraud”.

The fake self-portrait also appeared briefly on the cover of another book. Phaidon, one of the UK’s leading art publishers, used it in their 1947 edition. Vincent van Gogh: Paintings and Drawings. This book was introduced by the respected Austrian art historian Ludwig Goldscheider and his German colleague Wilhelm Uhde.

Naturally

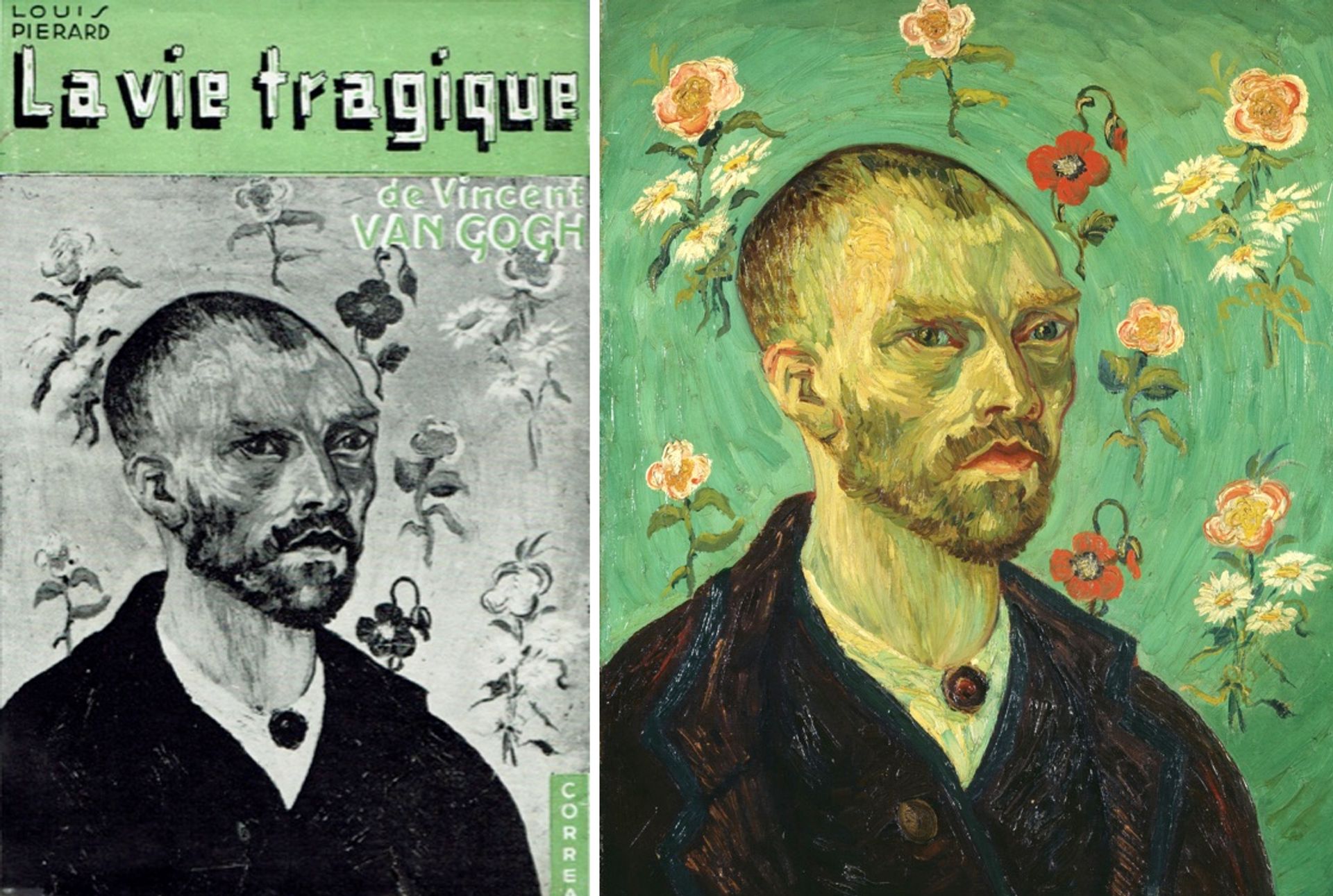

Cover by Heinz Lieser Vincent van Gogh: As seen by him (1963) and fake “self-portrait” (probably mid-1940s)

Bayer Leverkusen and private collection

This is the strangest of Van Gogh’s four fake self-portraits. It was used on the cover of Heinz Lieser’s book Only Vincent van Gogh himself, which was published in 1964 by the pharmaceutical company Bayer Leverkusen. Dedicated to self-portraits, the book contains 17 illustrations of actual works, although the author’s attestation damages the cover images.

The cover features an apparent self-portrait of Van Gogh, with the lower quarter of the painting only partially completed. At the bottom is what appears to be a line drawing of a Japanese actor and the inscription “etude a la bougie” (study by candlelight). The yellow-orange background is intended to suggest that it was painted by candlelight at night. The artist’s headshot is based on the Fogg Museum Self-portrait dedicated to Paul Gauguindespite appearing the other way around.

This self-portrait with Japanese motifs is said to have been found in a Paris cafe in 1948. The following year it was bought by the famous Hollywood producer William Goetz. He paid $50,000, a large sum at the time.

Shortly after the sale, the painting was rejected by specialists and by the end of the 1950s it had little support. It was left out of the reasoned 1970 de la Faille catalog. Now universally rejected, the photo apparently remains with the Goetz heirs.

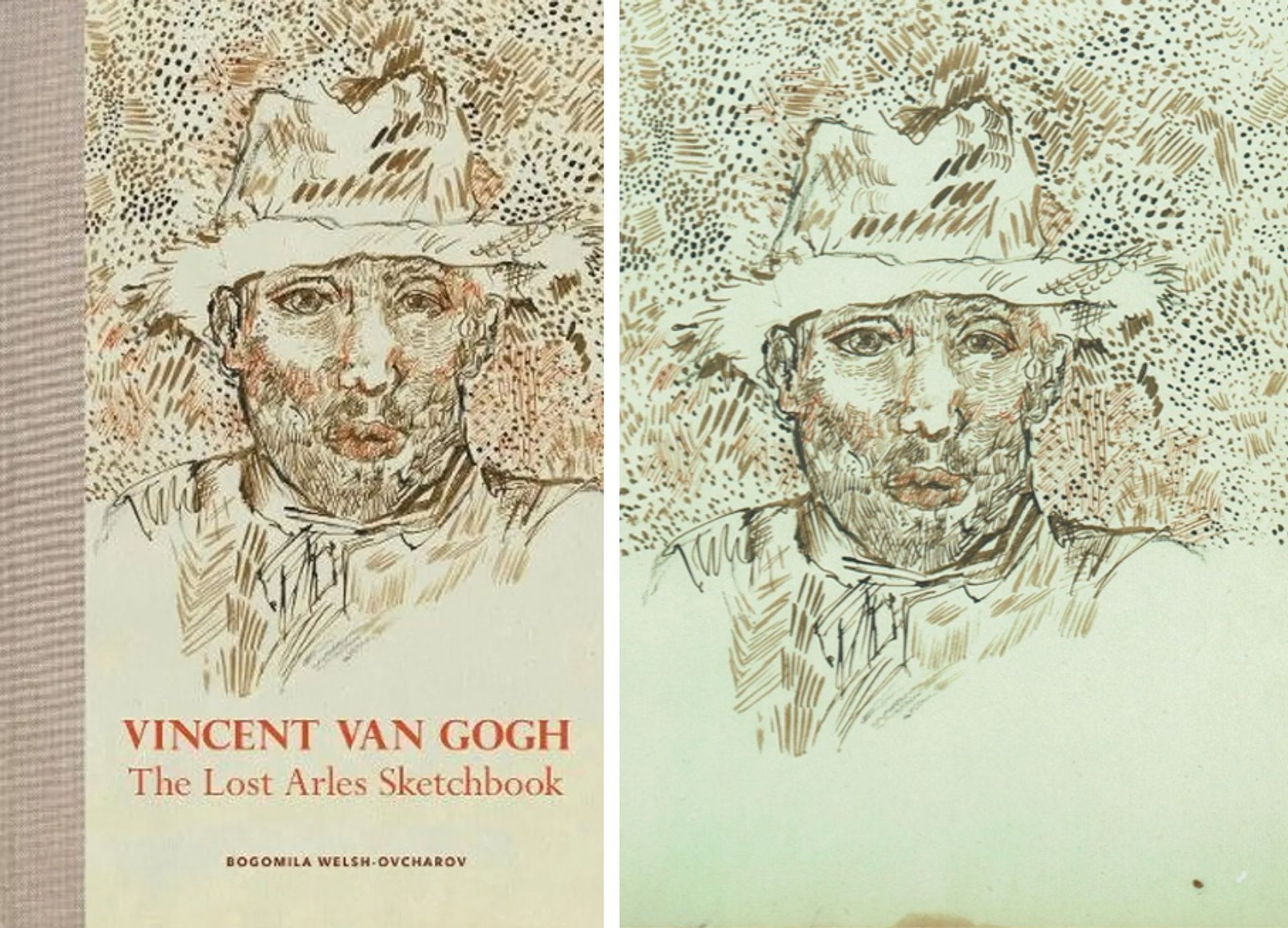

The Lost Arles Sketchbook

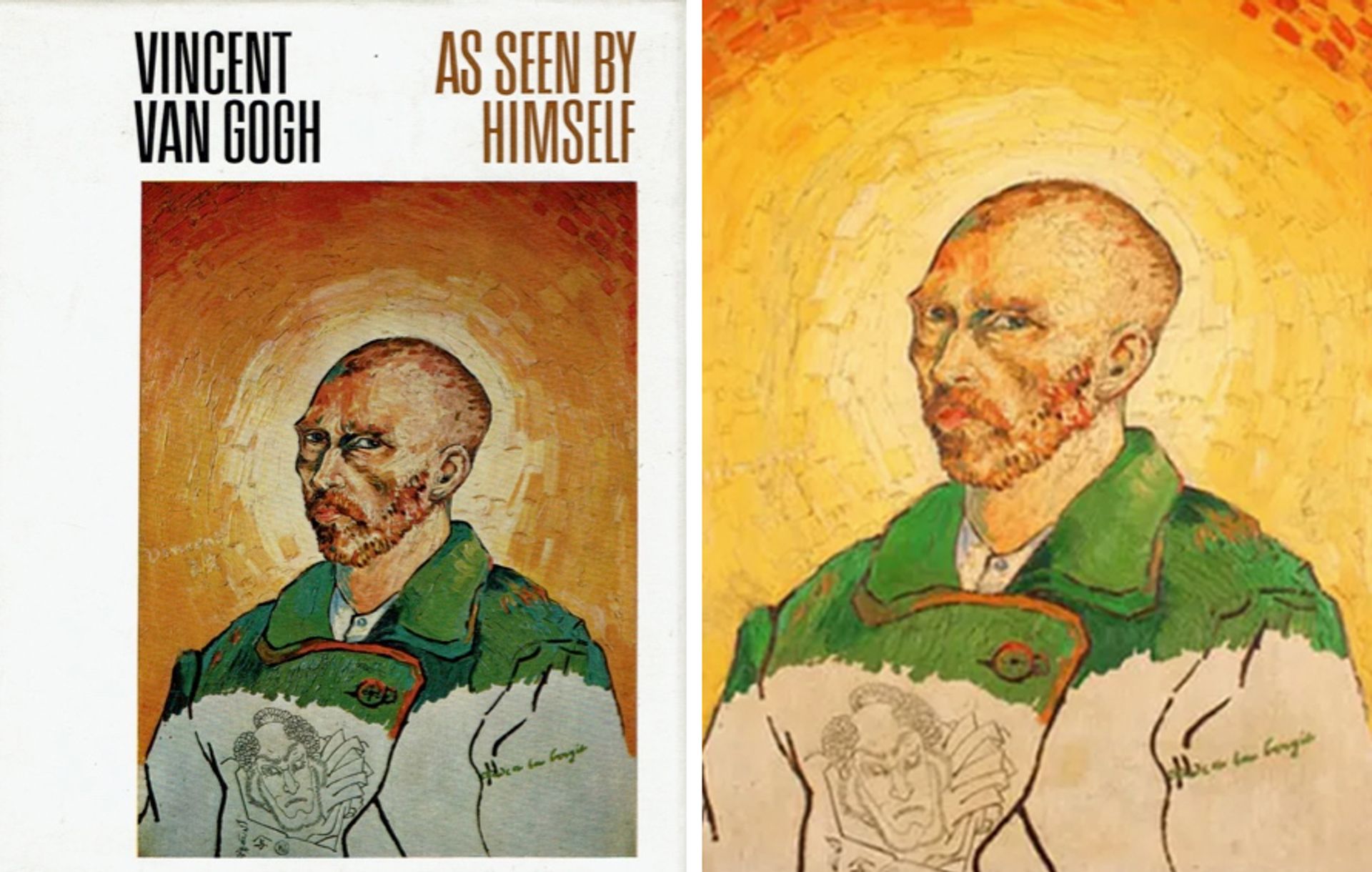

Cover by Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Sketch of Arles (2016) and fake “self-portrait” drawing (date unknown) Abrams, New York and unknown private collection

As recently as 2016 a fake self-portrait appeared on the cover Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Sketch of Arles, published by the respected Abrams imprint. The author is the well-known Canadian specialist Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov and the foreword is by the doyen of Van Gogh studies at the time, the late Ronald Pickvance of the UK. The large format book was released in English as well as French, Dutch and German.

Welsh-Ovcharov wrote that the 65 hitherto unknown drawings came from the sketchbook used by Van Gogh from May 1888, shortly after his arrival in Arles, to entering the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence asylum a year later. . The drawings are a mixture of landscapes and portraits, including a self-portrait, which was reproduced on the cover.

The book dates the self-portrait in ink to July-August 1888. According to Welsh-Ovcharov, “the artist, dressed in his trademark workman’s coat and iconic straw hat, renders his features and unshaven stubble with great spontaneity.”

The problem is that the entire sketchbook is a forgery, as the Van Gogh Museum has concluded and announced in a detailed statement.

“The Lost Sketchbook of Arles” is a salutary warning to publishers: beware of newly discovered Van Goghs that miraculously appear.