They are apparently art museums public spaces, but, in general, them to operate privately, like corporations, at least until the directors and their employees are safely retired. That is my experience as an outsider. When Thomas Hoving, director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1967 to 1977, published his 2009 autobiography, I was struck by his aggressive personal narrative. In the last chapter of the memoir he writes: “My low self-esteem was very clearly disguised in my constant display, my addiction to publicity and my intolerable ‘me-me-me’ attitudes and actions.”

I doubt that any of his descendants will publish such a personal and shockingly indiscreet account.

I live and work in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which is a good place for an art writer because of the local museum. The Carnegie Museum of Art is good enough to attract first-rate directors and curators – despite its high turnover rate – but small enough to be quite accessible to the pure academic. For more than 40 years, I’ve learned a lot about art museums informally by meeting curators, studying Carnegie shows, writing catalog essays, and participating in museum-organized public discussions.

The Andy Warhol Museum is a branch of the Carnegie, located a few miles from that institution, in a beautifully renovated seven-story building on the north side of Pittsburgh, within walking distance of downtown. The country’s largest single-artist museum, it houses a large collection of Warhol’s paintings, drawings and sculptures, as well as extensive archival materials. In some provinces In American cities in the 20th century At the beginning of the 20th century, the nouveau riche paid a lot of attention to art collecting. Cleveland, Ohio, with its amazing old master museum, is a prime example. In the late 1890s, Andrew Carnegie built a large museum building in Pittsburgh and organized the Carnegie Internationals, the second international survey exhibition to be established. He was not interested in organizing a permanent collection, although his museum later collected old masters and modernist art. Carnegie now hosts rotating shows, international and influential survey exhibitions. Pittsburgh plays an important role in the history of the American art museum world. It is the birthplace of the fortune that made possible the National Gallery in Washington and the Frick Museum in New York. But Carnegie, big and important as it may be, is clearly not of the caliber of those institutions, at least in terms of permanent collection.

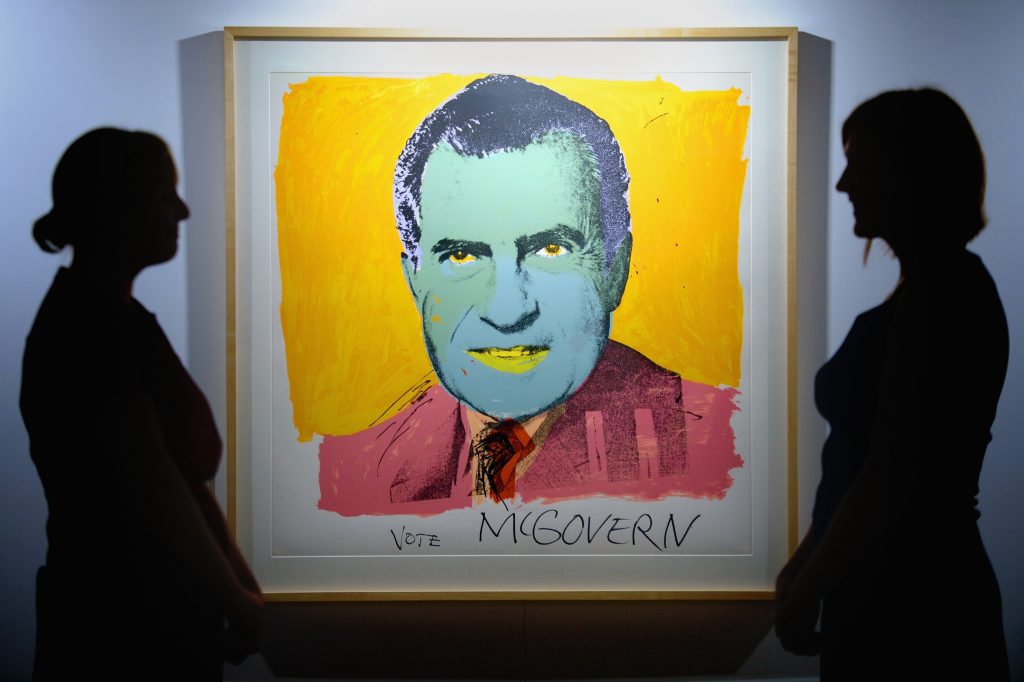

Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh in 1928. When he died suddenly in 1987, aged just 58, there was no plan for his estate, which included a large selection of his artworks and his city archives in Manhattan. He went to college in Pittsburgh, but rarely returned after moving to New York. And so there was a real need to commemorate the most famous artist of his generation here in his hometown.

Opened in 1994, the Warhol Museum houses a useful permanent exhibition of his major works, a changing exhibition of some marginal Warhol ephemera, exhibitions of other artists and his own archives. When I was writing a book about Warhol, I had access to the film archives. (And I was involved in a failed project to write about the archives.) I have visited Warhol often, and I often review his exhibitions. Because of Warhol’s great influence, it is the right place to show some contemporary artists, among them Deborah Kass and Firelei Báez.

Thanks to generous local foundations, Pittsburgh can support a major opera company and a first-rate symphony. A single-artist museum is a harder sell, at least when that artist is Warhol. The Gustave Moreau Musée in Paris has 1,300 paintings and 5,000 drawings by the French artist of the 20th century. In regular, limited doses, his art is a lot of fun. Warhol’s problem, by contrast, is that his art does not lend itself to extended aesthetic contemplation. Once seen Glitter Boxes or his soup cans once, you’ve seen enough. And while his archives are important, they are not yet organized in a way that supports scholarship. There are probably enough art history graduates and professors in Manhattan to support a major research institution devoted to Warhol. In Pittsburgh, they are not. And so the real question before Warhol in Pittsburgh was to find a role for such a museum. How can a monument be suitable for a great local artist?

At first, after 1994, I imagined doing shows like the Warhol Museum: “Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg: The first masterpieces” or “Warhol/Jeff Koons/Cady Nolan: Postmodern Pop Art“. Or – why not? —“Camille Pissarro/Chaim Soutine/Warhol: Three Urban Visions“. These exhibitions would attract a large number of local and out-of-town visitors. But it would be expensive to organize. And while there’s nothing wrong with a museum with a relatively small audience, Warhol has yet to define a clear mission for himself. If Warhol’s legacy had been absorbed into Carnegie, there might be only one gallery dedicated to his artwork. However, since the museum occupies a large building, the situation is more complicated.

Therefore, it is not surprising that there has been some controversy in the press recently. Several employees left, the museum made a controversial loan of works for an exhibition in Saudi Arabia, and most recently, director Patrick Moore, who had ambitious plans for the museum, has left. As I stated in an opinion piece for this publication on the loan to Saudi Arabia, I believed that art museums owe their public a better accounting. The Warhol Museum, like any such establishment, is a semi-public institution to the extent that it depends on our funding. That is my naively optimistic belief. As someone who admires this museum and appreciates the work of its staff, I really hope it eventually finds its way.