Wine labels often display information mandated by legislation or regional requirements. However, that space above a bottle has infinite possibilities for design and semiotics. There are as many labels as there are wines and producers. Just as we know not to judge a book by its cover, scholars have also learned not to judge a wine by its label. The exceptions to this rule are the First Growth wine labels of Château Mouton Rothschild, which not only introduced important changes in the production of fine wine, but also created the standard for the way these wines are presented to the world. the design of a bottle—and how it communicates what’s inside—into an art form.

Wine labeling is as old as the drink itself. There is evidence dating back to 1352 BC of wine jars with papyrus labels in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the farm, the region and even the winemaker. A millennium later, in the Persian empire, labeling accelerated to cover new varieties from Greek and Phoenician growers. In the 19th century, a Benedictine monk and cellar master, Dom Pierre Pérignon, attached handwritten labels to the bottles by string. The invention of lithography led to the first paper label in Germany in the 1780s, and the practice flourished.

In Bordeaux at the turn of the 20th century, Mouton Rothschild’s wines were already highly sought after and respected in the industry, but were not yet classified in the strict Bordeaux Classification of 1855. In 1922, he was considered an outsider and a novice by the Médoc traditionalists. He began to make changes in the production and marketing of wine. These were later adopted by the global wine industry, and are perhaps taken for granted by oenophiles today.

For example, until 1922, the castle’s wine was sent in barrels to Bordelaise merchants to be bottled for each producer. Baron Philippe decided that the estate could do it himself and inaugurated the practice “bottled in the castle“— bottling, labeling and storing the wine in the cellars. This allowed the family to oversee and control the quality and production of the wine, from the vineyards to bottling, and make a compelling marketing case for all stages of wine production. 84 hectares of the estate.

Baron Philippe wanted to mark this change by commissioning a new label for the wine. He asked a young artist and graphic designer, Jean Carlu, to make a label. Carlo had already produced commercial work, mainly theater posters and advertisements, and had won awards—achievements achieved with one arm, having lost the other in a tram accident. Carlu’s work was related to the main art movements, starting with Art Deco, Cubism and Surrealism. Its label incorporated the Rothschild family’s five-arrow crest and ram’s head mask as a statement of intent in bold, modern typography.

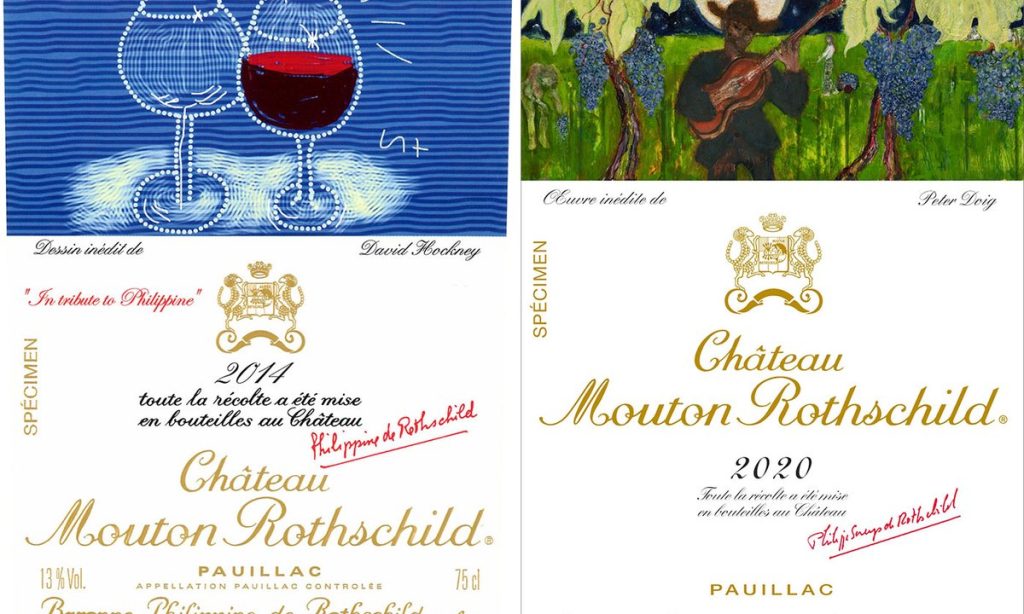

The Bordeaux wine trade did not take over Carlu’s label, but the family continued to produce wine. During World War II the family had to flee to Lausanne, and the commissions ceased until 1945, when another young artist, Philippe Jullian, was asked to restart the process, celebrating the end of the war with a V for Victory. label In the following decade, thanks to Baron Philippe’s daughter, Philippine de Rothschild, who had a successful career at the Comédie-Française, a group of artist friends from the theater world designed vintage labels, including Jean Cocteau (1947), Léonor. Fini (1952) and Jean Hugo (1946). In 1955, when Georges Braque approached the château and asked him to design a bottle, the practice became a “game changer,” according to Julien de Beaumarchais de Rothschild, the youngest of the three siblings who now run the château. Suddenly, prejudices about artists designing practical, mass-produced objects like wine bottles were dispelled. “Art came to help us and be our partner in this adventure,” says Julien. It helped that the wines were considered world class.

The label artists became friends of the family, and the progression of the vintage shows not only the development of the family’s wine, but also their tastes in art. Baron Philippe included Salvador Dalí (1958), Henry Moore (1964), César (1967) and Joan Miró (1969), among others. Max Ernst was commissioned to produce the 1965 stamp, but instead gave the project to his wife Dorothea Tanning. He produced a row of five rams in a delightful line dance.

After the passing of Baron Philippe, his daughter Philippe seemed to have charmed her way into the hearts of many important 20th-century modernist artists, including Georg Baselitz (1989), Francis Bacon (1990) and Lucian Freud (2006). The family has collected letters, anecdotes and archives about each artist and their friendship with the matriarch. Stories include how he followed Balthus for years to design a label. He commissioned the pincer movement to his wife Setsuko Klossowska de Rola to design the 1991 vintage. Balthus eventually agreed and produced a drawing for the 1993 vintage that featured the artist’s signature nude young woman. The label was banned in the United States and an alternative was released, with a white space where the image should have been.

Relationships between artists and family worked because they were based on admiration and friendship. Artists were never chosen because they were famous or trendy. This continues today, with Julien responsible for the artistic direction and liaison of the winery. “We believe that artists should have complete creative freedom,” he says. “That’s why we don’t impose any size restrictions on those who collaborate. The works can be huge, such as Karel Appel’s (1994), or small, such as Hans Hartung’s (1980). Every year, artists take ownership of the space and own it in their own way.” Ideally, the family doesn’t want to “create controversy”, and they should be sensitive to the markets. Even with this freedom to decorate the labels, almost every artist has chosen to interpret an element of wine, vineyard, grape or wine drinking in this decades-long tradition.

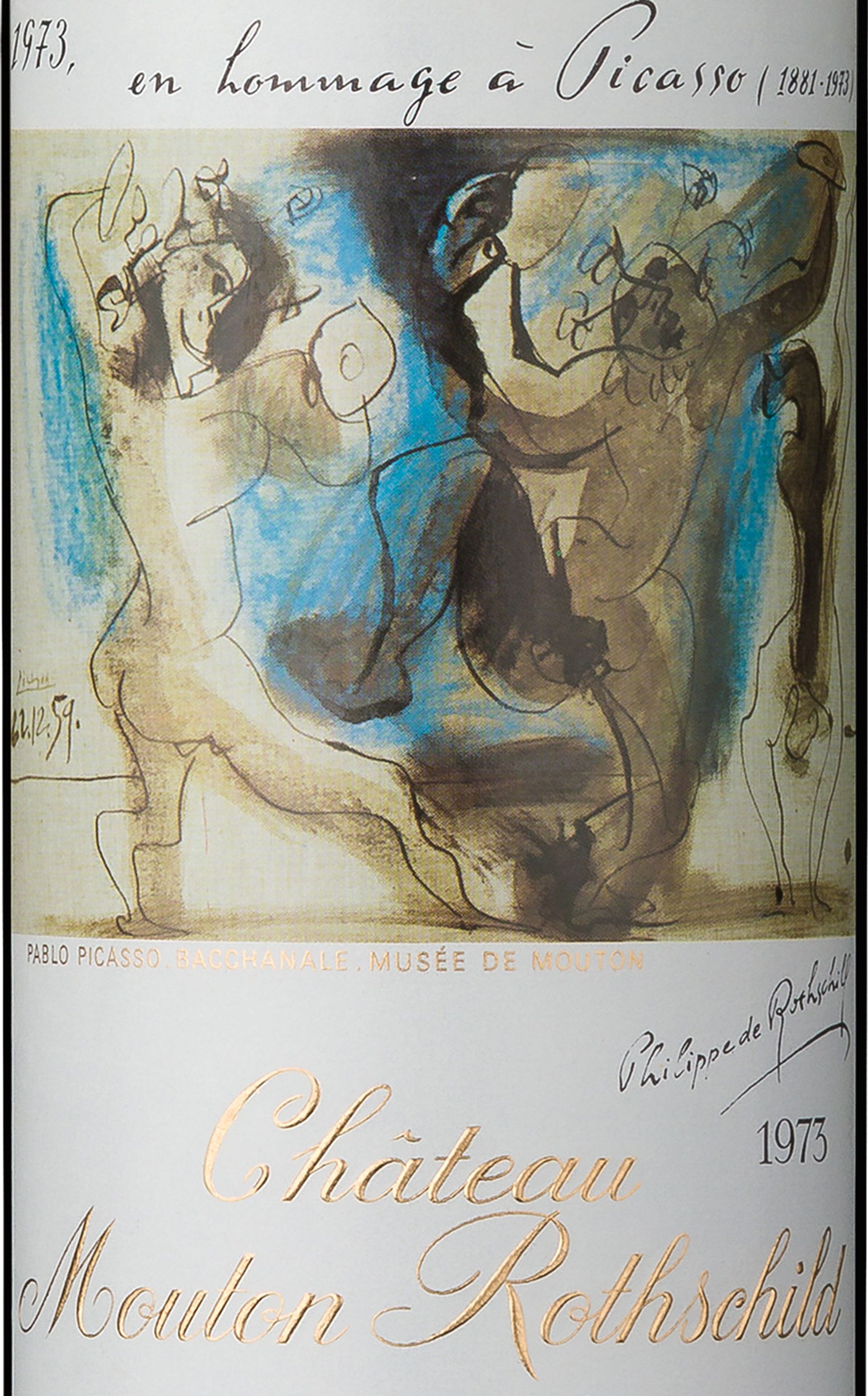

1973 Pablo Picasso tribute stamp for Château Mouton Rothschild Château Mouton Rothschild

After all, the castle has been able to combine artistic excellence with winemaking excellence and maintain that distinction by being innovative in the industry. And he has brought artists from all mediums into the story to heighten the message and symbolism of a pioneering approach to winemaking. “The artists who illustrate the labels are not only painters,” says Julien. “There are also sculptors, such as Bernar Venet (2007), or scenographers, such as Robert Wilson (2001). We love the diversity of these artists and their media. I was delighted when David Hockney (2014) created his work on an iPad.’

Such stories are on display in the family’s Paintings for the Labels room, since 2013 in the premises of the Pauillac castle, which was relaunched in 2020. Open to the public, the museum houses all the original artwork that informed the label, the original label designs, which toured to more than 42 cities worldwide since 1981. The space has been re-imagined under Julien’s artistic direction, with Francis Lacloche-designed displays filled with sketches, handwritten notes, archival photos and original artwork of all vintages. The museum is a survey of the best artists of the 20th century – Picasso, Dalí, Miró, Warhol, Freud, Bacon – with notable contemporary artists such as Gerhard Richter and Anish Kapoor.

Perhaps drinkers will fully understand the importance of this balancing act when they enjoy this Bordeaux First Growth. Undoubtedly, the combination of creative excellence and commercial success makes it truly the first luxury wine. As Julien says, “This broad vision of culture, which Mouton Rothschild reflects in the union of its wine and the Paintings for the Labels exhibition, offers the appreciator a high level of pleasure for both the eye and the palate. With each vintage, the works created by great artists for our stamps show us the perfect union of what the ancient Greeks called the beautiful and the good. kalos kai agathos [beautiful and good]”.

Mouton Rothschild also developed the Bordeaux winemaking business through his eccentricity and following his vision in this strict appellation. This independent spirit was finally rewarded when the winery was elevated to the highest distinction of Premier Cru in 1973, after decades of lobbying by the family. It was the year Picasso died, and the family honored both milestones by asking his widow, Jacqueline Roque, to choose a work to decorate this holding.

Contemporary artists continue to celebrate wine and take commissions alongside Julien. The 2019 vintage was decorated by Olafur Eliasson, who was “fascinated by the Rothschild family’s long history of working with artists” and wanted to be part of that tradition – or, as he put it, “as part of a river. Many of the artists here are inspiring, because together they have shaped the river that I am now a part of.’

Peter Doig (2020) took on the task because he wanted to “capture an ode to the magic that goes on behind the scenes in the production of this wine”. Chiharu Shiota, in his depiction of the final harvest of 2021, honored the emotions we feel when we are connected to the growing seasons in a vineyard.

In the same way that perfect exploitation is the result of the conditions of the vineyard and all the natural skills of human manipulation, the collection of art cannot be repeated because it is a response to a particular time and territory. “If someone tried to restart what was done in Mouton from 1945, it would not be possible,” says Julien. “You wouldn’t respond to specific vintages or specific artists like they do. What is made is unique for each harvest and for each time and place.’

However, there are plenty of examples of wineries today making it essential to include artists on their labels, from Australia to Lebanon to Chile. All credit Château Mouton Rothschild for inspiration and for breaking and reshaping the rules in a system where art is as much a part of expression as wine tasting notes. Mouton Rothschild, meanwhile, will continue this project into the next century. “I hope that this adventure between Château Mouton Rothschild and art will last as long as possible,” says Julien. “But more than anything else, I hope that in 100 years Mouton Rothschild will continue to produce as fine wines as they do today.” Given the castle’s commitment to good taste, in or on the bottle, that expectation becomes a guarantee.

- chateau-mouton-rothschild.com

All material © Show Media Ltd